Table of Contents

Introduction

An introduction to the book of Isaiah, the book of Isaiah stands as a towering mountain in the midst of the biblical landscape! The events of Isaiah’s life, his testimony, his prophecies, touch all of Scripture, the past, present, and future in biblical history. The most significant aspect of the book of Isaiah is his prophetic message of the promised Messiah! The approach we are going to take to the study of the book of Isaiah, is from a Torah perspective and try to look closely at the semitic languages: the Hebrew and Aramaic translations. Aramaic is considered a Semitic language, as are many other languages. Both Hebrew and Akkadian are also Semitic languages, including Ugaritic. These are what are known as cognate languages. A cognate language is one that shares certain characteristics regarding morphology (word structure) and syntax (arrangement of words in sentences). Hebrew and Arabic share morphological, phonetic and semantic features. Another example is found in the classification of Spanish, French, and Portuguese as Romance Languages all of which go back to Latin. Generally speaking, when someone knows one of these languages, it is easier to learn the others. This is because of the family characteristics they share. The same relationships are found in Hebrew and Aramaic Semitic languages. Note that even though there are similarities between languages, such as in morphology, syntax, and vocabulary, this does not mean these things hold up in all cases. An example of this may be taken from Modern Hebrew and biblical Hebrew. Speakers of Modern Hebrew will read the Tanakh and occasionally mistakenly read a word assigning it the modern meaning. However, the meaning of a word may have changed over the centuries from the time the Scriptures were written.

The hermeneutic approach we will take for studying the book of Isaiah: (i) we will look at the Semitic languages, Hebrew and Aramaic, and examine the theological, historical, moral, and spiritual perspectives. Occasionally we will draw upon the Greek (septuagint) translation of Isaiah, coupled with the Targum Jonathan to draw out a Jewish perspective, and discuss how these are related to the Christian perspectives, and the messianic prophecies found in Isaiah. This will be a verse-by-verse exposition of the Isaiah text. (ii) We will look at the Rabbinic literature usage of Isaiah, from the Talmud, Midrash, and Jewish commentators, and how they interpret the book of Isaiah, and draw out their interpretations on the exhortations of Isaiah and his time, with a practical application today for our lives as we live in an ever increasingly evil world.

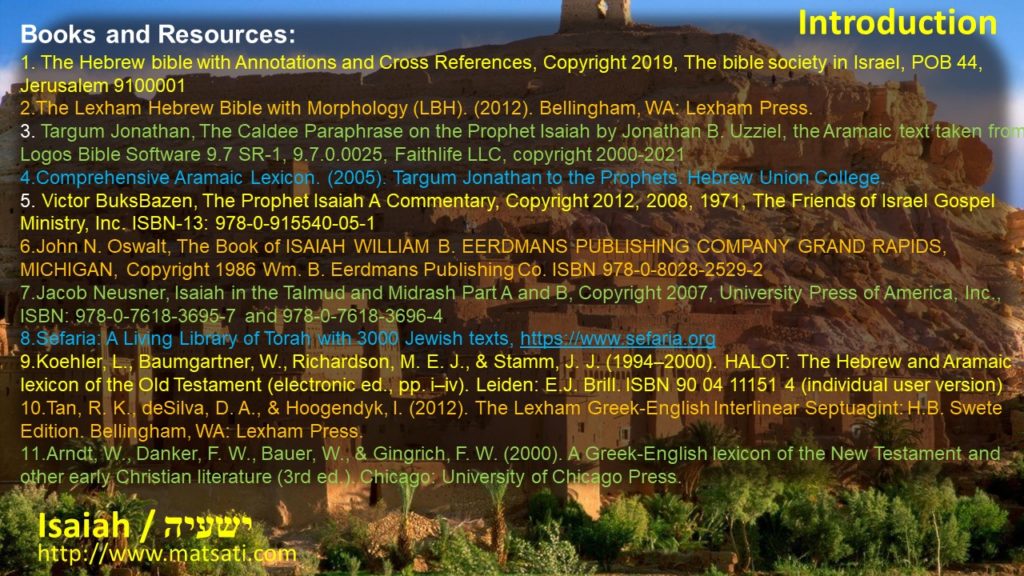

The following resources will be used during this series of studies.

Books and Resources:

- The Hebrew bible with Annotations and Cross References, Copyright 2019, The bible society in Israel, POB 44, Jerusalem 9100001

- The Lexham Hebrew Bible with Morphology (LBH). (2012). Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

- Targum Jonathan, The Caldee Paraphrase on the Prophet Isaiah by Jonathan B. Uzziel, the Aramaic text taken from Logos Bible Software 9.7 SR-1, 9.7.0.0025, Faithlife LLC, copyright 2000-2021

- Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon. (2005). Targum Jonathan to the Prophets. Hebrew Union College.

- Victor BuksBazen, The Prophet Isaiah A Commentary, Copyright 2012, 2008, 1971, The Friends of Israel Gospel Ministry, Inc. ISBN-13: 978-0-915540-05-1

- John N. Oswalt, The Book of ISAIAH WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN, Copyright 1986 Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8028-2529-2

- Jacob Neusner, Isaiah in the Talmud and Midrash Part A and B, Copyright 2007, University Press of America, Inc., ISBN: 978-0-7618-3695-7 and 978-0-7618-3696-4

- Sefaria: A Living Library of Torah with 3000 Jewish texts, https://www.sefaria.org

- Koehler, L., Baumgartner, W., Richardson, M. E. J., & Stamm, J. J. (1994–2000). HALOT: The Hebrew and Aramaic lexicon of the Old Testament (electronic ed., pp. i–iv). Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90 04 11151 4 (individual user version)

- Tan, R. K., deSilva, D. A., & Hoogendyk, I. (2012). The Lexham Greek-English Interlinear Septuagint: H.B. Swete Edition. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

- Arndt, W., Danker, F. W., Bauer, W., & Gingrich, F. W. (2000). A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

The word Targum means “translation” and generally refers to any translation of the Hebrew text into another language such as English, Spanish, Greek, Aramaic, etc. Over time however, the word Targum has come to refer primarily to the Aramaic translation of the Tanakh. There are a very large number of people who translated the Hebrew Bible into Aramaic tongue as determined from archeological finds and demonstrated by the numerous fragmented texts. There are however two major Aramaic translations that are complete, translated by Onqelos and Jonathan ben Uzziel. Targum Jonathan is roughly contemporary with the Targum Onqelos but with extensive interpretation material that is added to the text. These two texts are especially noteworthy as they are represented in the rabbinic literature. The purpose of the Aramaic translation is given to us according to Ezra 4:7 and Nehemiah 8:8. Ezra records how Aramaic was the language of the king of Persia and surrounding areas Ezra 4:7 And in the days of Artaxerxes, Bishlam, Mithredath, Tabeel, and the rest of his colleagues wrote to Artaxerxes king of Persia; and the text of the letter was written in Aramaic and translated from Aramaic. (NASB) We are told in Nehemiah that the priests would read from the Torah and interpret on the fly in Aramaic so the people could understand according to Nehemiah 8:8. So they read in the book of the law — To wit, Ezra and his companions, successively. And gave the sense — The meaning of the Hebrew words, which they expounded in the common language — And caused them to understand the reading — Or that which they read, the Holy Scriptures. This is likely the reason why the aramaic paraphrase expands so extensively on the original Hebrew text. According to Nehemiah, it was at this point it became the custom of repeating and explaining the Hebrew sacred scriptures in the Aramaic tongue following the exile. We see according to Nehemiah the Aramaic translation was originally and oral exposition. Gradually this was written in text form. The Targum to the Prophets by Jonathan ben Uzziel is the Targum we will be using throughout this study. Jonathan ben Uzziel was a disciple of Hillel. Targum Jonathan is much more paraphasic as compared to Onqelos.

We are going to look at the grammatical-historical exegesis of the text as prophecy is best understood in this manner. We will make the effort to try and understand what the author Isaiah meant by his words in his contemporary time. If he is using metaphorical language, we will seek the meaning of the metaphor. In the prophetic text from Isaiah, there is in some cases a modern day fulfillment, and then a future expectation of what is to come. The author’s intention is based upon the analysis of the language. The literal fulfillment of a prophecy in both the present day and in the future expectation, will be approached by stressing the normal meaning of the words in their grammatical-historical context. This will help to provide a broader interpretive focus on the words of Isaiah. In terms of prophecy, we read the author of Hebrews 1:1-2 stating the following, “God, after He spoke long ago to the fathers in the prophets in many portions and in many ways, in these last days has spoken to us in His Son.” This provides us with the concept of progressive revelation. This teaches us that the NT was not created in a vacuum, but necessitates that we must study the Tanakh (OT) text looking in a forward direction. The NT text also provides us with an interpretation of the Tanakh, which is also important to study the first century understanding. These things demonstrate the continuity between the Tanakh and the NT eras, in the sense that we look to the NT text as the completion of the prophetic meaning from the Tanakh, that the Kingdom of God goes unaltered, as God never changes, and His Word is established forever! (Isaiah 40:8) We will try to understand how the different portions of the Isaiah text come to be used in a prophetic sense. The NT text brings clarity as a guide for the more obscure texts, which remain vague until we study the later NT revelation. We also want to be careful not to hold to a very strict literalism on the details of a prophecy as this can have the possibility of producing a misconception in prophetic expectations as the unbelieving Jews have concerning the Messiah. We will take a grammatical-historical approach as this will help us to fully understand the meaning of the Isaiah text, and couple this with the interpretations of the NT. The hope is to be able to understand both the contemporary fulfillment and the future expectation.

The Hebrew text of Isaiah, in spite of some minor differences in the ancient manuscripts, has been preserved remarkably well. The differences are the result of copyist errors. The Sofer is an professional copyist of the Hebrew manuscript who take great care and painstaking devotion to preserving the text. The weightiness of this profession is if one error enters into the text, this could render the whole book unkosher for use in the synagogue. It is important to note that the two manuscripts of Isaiah recently discovered in qumran are over 1000 years older than what we currently have in the Masoretic text. The earlier manuscripts are essentially the same as what we have, a testimony to the skill of the soferim. The two qumran texts 1QIsa-a and 1QIsa-b date back to the first century BC. The accuracy of these texts is a testimony to the Jews who were the faithful guardians of God’s word, meriting much gratitude to those of us who lived many centuries later.

Historical Context of Isaiah

The Hebrew prophet Isaiah ministry was active during the time period of 740-701 BC. His name ישעיה (Yeshayah) means “God is salvation.” His name alludes to the major teachings Isaiah will be teaching the people. Isaiah lived in Jerusalem and he referred to his wife as the prophetess giving his two sons the names שְׁאָר יָשׁוּב (Shear-Jashub) meaning “a remnant will return” and מַהֵר שָׁלָל חָשׁ בַּז (Maher shalal has baz) meaning “he has made haste to the plunder.” These names were given to be symbolic of his prophecies, the first was intended for Israel to return to faith in the God of Israel, the second was possibly intended as a warning to Peka, the person put in place as king of Israel, and Rezin the king of Aram (Syria). They besieged Jerusalem (734 BC) in an attempt to dispose of king Ahaz who refused to join them in their alliance against Assyria. Isaiah was called to prophecy in the year of King Uzziah’s death (740 BC) which came via a vision in the Temple.

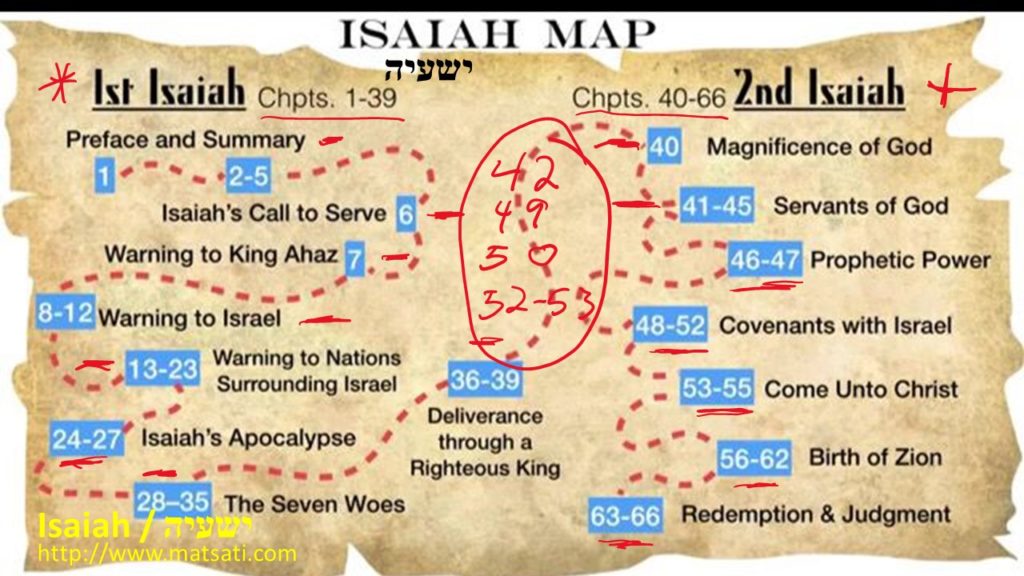

The historical setting of the book of Isaiah provides us with the background for his message, and this is essential for understanding his message. The uniqueness of Isaiah’s book is that it covers a wide span of Israel’s history, beyond the ministry of Isaiah, from 740 to 701 BC. The reason this is significant is that Isaiah 1-39 describes the events during Isaiah’s lifetime. Isaiah 40-66 describes future events. Because of this, multiple theories have been raised as Isaiah being written by multiple authors. There are three historical settings, (i) the Period of Isaiah’s lifetime (740-701 BC), Isaiah 1-39, (ii) the period of the exile (605-539), Isaiah 40-55, and (iii) the period of the return (539-500 BC), Isaiah 56-66. These are perplexing theories. Based upon Isaiah 1:1, it would appear there is a claim that everything that follows is from Isaiah the son of Amoz. Note that Isaiah 2:1, 7:3, 13:1, 20:2, 37:6, 21, and 38:1 words are attributed directly to Isaiah. While on the other hand, Isaiah is not named as the source of any of the materials in chs. 40–66. The burden of proof however is on those who propose other sources as no source is mentioned in Isaiah 40-66. For this study, we will assume that Isaiah was the author of the entire book of Isaiah, chapter 1 through 66!

The Time Span 739–701 B.C.

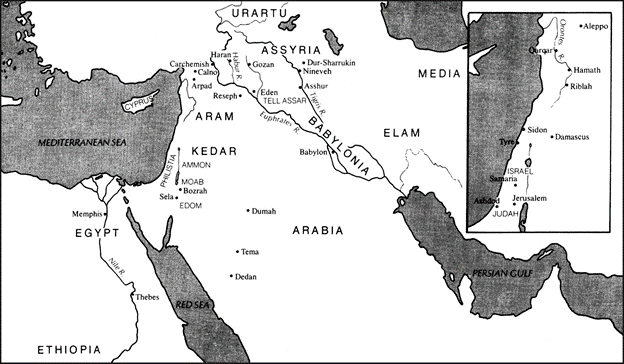

In the time frame between 739-701 BC this spans Isaiah 1-39, and Assyria experienced its last period of greatness. This period of greatness ended with the destruction of Assyria by Medo-Babylonia in 609 BC. The Assyrian homeland was located in northern Iraq along the Tigris River. Asshur and Nineveh were the two major cities in the Assyrian empire. Assyria extended its empire southward down the Mesopotamian valley toward Babylon and the Persion Gulf, and westward towards the Mediterranean.

The Northern kingdom of Israel was ruled by a man named Jeroboam; he was the second Israelite king to bear this name. (2 Kings 14:23-29) The southern kingdom (Judah) also had a single monarch, King Azariah or Uzziah. (2 Kings 15:1-7, 2 Chronicles 26:1-23) The northern kingdom’s relative peace lead the people to become complacent in their relationship with God, they served and worshiped other gods. The prophets Amos and Hosea were sent by God to reprove Israel of their sins and call them to seek God in heaven. Israel would not listen and continued in their sinful ways and led to their destruction. The southern kingdom on the other hand, Judah, was somewhat less corrupted. Uzziah however did attempt to act as a high priest according to 2 Chronicles 26:16-21. He is, however, described as a faithful king. The sin of Israel is clearly defined according to Hosea 1-3 and then in Ezekiel 16 and 23. They are called prostitutes who debase themselves with unworthy lovers for gain. This is synonymous to “forgetting God” according to Devarim / Deuteronomy 8:11. The people forsook their trusting in God by serving other gods they had not known. Because of this the prophets and the rabbinic literature implicitly link idolatry, adulter, and oppression together as one.

In 735 BC, Peka King of Israel, and Rezin king of Damascus, mounted an attack against Judah (2 Kings 16:5, 2 Chronicles 28:5-15). It is possible there was a joint attack from the Edomites and the Philistines as well. (2 Kings 16:6, 2 Chronicles 28:16-18) Or, knowing Judah’s military was busy with fighting against the kingdoms of the north, they took advantage? Because of these things, Ahaz was afraid of the Assyrian-Israelite threat (Isaiah 7:2) and so he sent to Tiglath-pileser for help. (2 Kings 16:7-9) These events led to the first phase of Isaiah’s ministry. Isaiah saw Judah become more involved in politics and power, as opposed to trusting in God. (Isaiah 1:21-23, 2:12-17) Assyria was no friend of Judah, they would take what Judah gave them, and then take more from the nation by force. (Isaiah 8:5-8) Eventually Tiglath-pileser conquered Pekah and destroyed Damascus (723 BC). Ajax was called to stand before Tiglath-pileser and enter into a covenant even more binding which required recognition of the Assyrian gods. (II Kings 16:10-16, 2 Chronicles 28:20-21)

The Scriptures consider Hezekiah a good king, one who sought to cleanse the land of Idolatry and the temple of pagan worship. King Hezekiah also sought to establish the Torah (2 Kings 18:1-6, 2 Chronicles 29:1-36). He also extended the borders of his kingdom. (2 Kings 18:8) Hezekiah also called the people of northern Israel to come to a Passover (2 Chronicles 30:1-5, 10-11). The idea of inviting Israel to passover demonstrates his vision for the nation to return to God. Scholars are not certain to what extent Hezekiah was involved in the confederation formed against the Assyrian from 715 to 713 BC by the Philistines and South Syrian area. (Isaiah 14:28-31, 17:14, 20:1-6)

Sargon II was the successor of Sennacherib born in 762 BC. In 710 BC he was in a position to fight against Babylon and so started a war campaign against Merodach-baladan and defeated him. As a result of his victory he got world dominance. He gained a lot of pride from this victory as his enemies lay at his feet. He considered himself Dur-Sharrukin “mountain of Sargon” believing himself to be very mighty. This is the man being described according to Isaiah 14. Sargon was killed on the battlefield and disgraced and forgotten. His death led to great joy in the hearts of those who were oppressed by Assyria. In 710 BC Babylon come down to Judah (Isaiah 39:1) and Hezekiah made an alliance with Philistia, Edom, and Moab. This playing politics with the nations was an affront to God that had extreme consequences. (Isaiah 22:5-14, 29:15-16, 30:1-18)

Sennacherib became the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire following the death of his father Sargon II in 705 BC and Sennacherib died in 681 BC. In the third babylonian campaign, Sennacherib came down the coast of the Mediterranean to Tyre. The city was captured and a new leader was put in place on the throne. Tyre never again gained its strength and power following this invasion. Sennacherib then attacked the Philistine cities of Ekron and Ashkelon. The babylonian army began then to move inward to attack the fortresses of Judah that were in the rolling hill country between Philistine plain and the central ridge, such places as the stronghold of Lachish. (2 Kings 18:13) Hezekiah had made an agreement with Egypt, and it is unclear of Egypt helped at this time. The annals of Sennacherib reports that the Egyptian attack took place before the attack upon Ekron and Ashkelon. The speech given by Rabshaqeh outside of Jerusalem mentioning Egypt (Isaiah 36:1-20) Note that according to Isaiah 37:9 we read that Sennacherib was concerned about a possible Egyptian attack and so he wrote a letter to follow up Rabshaqeh’s visit. Therefore, the Egyptian battle must have come subsequent to the Rabshaqeh’s visit and the fall of Lachish.

Scholars disagree about what happens next, but all agree that Hezekiah paide Sennacherib a very large tribute for the Assyrian army to return home. Sennacherib left Jerusalem, which was uncharacteristic of his modus operandi, he would generally depose the existing king and place a compliant king in his place. He left Hezekiah in place, however. The biblical account has a God given plague killing many in the Assyrian army, forcing their retreat. Scholars say that this plague was not me in the annals of the Assyrians, but we have the biblical accounting. This account in and of itself proves the wisdom of trusting in God! Nonetheless, the Assyrian officer appeared outside the gates and demanded full capitulation with consequent deportation (Isaiah 36:16–18). Acting on encouragement from Isaiah, Hezekiah refused to do so.

The Time Span 605–539 B.C.

This time frame spans Isaiah 40-66. Note that chapters 40 through 66 do not correspond to specific historical events like those from Isaiah 6-39. Isaiah 40-66 can be divided into two groups, (i) chapters 40-55 seem to offer hope to a people in exile, and (ii) chapters 56-66 appear to speak to the people who have returned to the Land. Babylon succeeded Nineveh as the ruling city of the world empire by 605 BC. A coalition of Babylonia and Medo-Persia (the Medes being a more northern group, and the Persians a more southern group, from the mountainous regions east of Mesopotamia) combined to topple the Assyrian empire, or its remains, in 609. At first the Babylonians were the dominant figures in the alliance. Thus they took the richer, southern parts of the Assyrian corpse, while the Medes took the sparser, northern parts. This Neo-Babylonian empire (650–539 B.C.) was a brief interlude in a much larger movement, the Medo-Persian one. These people never intended to be satisfied with the outer edges of the Assyrian spoils, nor did they intend to have a larger portion, they intended to have it all. Thus they only bided their time under the strong Babylonian monarch Nebuchadrezzar and his progressively weaker successors until they were ready to move. In 539 B.C. they ushered in what is known as the Persian empire.

The Judean exile was confined to this time period of Babylonian power. Babylon continued the Assyrian policy of deportation of the people, where the people were exiled to a distant land where they were less likely to create a rebellion. This deportation of Judeans occurred prior to 586 in 598 BC (2 Kings 24:8-17). With the destruction of Jerusalem, there was another more extensive deportation of people. (2 Kings 25:8-21) Because of this, Isaiah 40-55 directly addresses this situation of the loss of faith due to exile. Isaiah tells the people that God has not abandoned them but has chosen them. The point is that God is still able to deliver the exiles, he is still able to deliver from sin, and bring the people back to the Land. We note the power of God, as no other nation has ever returned, except Israel! God’s promises always come true and are entirely trustworthy!

King Cyrus brought in a new foreign policy. He completely reversed the previous policy, granting exiles to return home and offering imperial funds for the rebuilding of the Temple, etc. (see Ezra 1:1-4) This was undoubtedly the result of God working in Cyrus’ heart. Something to note that Cyrus giving money for the rebuilding of the Temple, was consistent with the Middle eastern belief that these other gods worked in conjunction with the God of Israel. The belief was that Marduk, Ashur, Bel, Amon-Ra, and Hashem (YHVH) were all manifestations of the one God. This couldnt be farther from the truth, and Isaiah states this with a resounding NO! Note Isaiah 45:4–5, states “I have surnamed you, though you knew me not. I am the Lord, and there is no other; beside me there is no God. I will gird you, though you knew me not, that men may know from the east and from the west, that beside me there is none.”

The Time Span 539–400 B.C.

The exile of Israel extended up until 539 BC, long after Cyrus’ decree they could return. Zealous Jews such as Zerubbabel and the high priest Jeshua (Ezra 2:1-2, 3:1) started the long journey back to Judah and Jerusalem. According to Ezra 2:64-65, there were approximately 50,000 people who were invited to return. The idealized vision of “the promised Land” probably fueled the move. Note how once they returned, they were not welcomed with open arms. They were in fact treated with hostility and suspicion. The work to build the second Temple began and then quickly ended, it wasn’t until 20 years later that the work would begin again with the prophets Haggai and Zechariah were able to get the people to consider their faith in the God of Israel to begin the world again. In 516 BC the work was completed. It was no comparison to Solomon’s Temple, however. The efforts of these prophets, Haggai and Zechariah were to a very difficult people, since 75 years later, when Ezra and Nehemiah came on the scene, it was by their efforts the national identity returned as the people of God. At this time, Judah had depended in part on the Persian empire and functioned as a satrap (a provincial governor). The capital of this satrap was possibly located in Damascus. Under the satrap were local governors, as indicated by Ezra 4:17, where the governor is in Samaria, and Nehemiah.5.15, where Nehemiah is appointed governor of Judah. Taking the prophets Haggai, Zechariah, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Malachi, it is possible to reconstruct the religious life of Judah during this period of time. In general three groups can be identified, (i) those who were deeply concerned about God and the relationship of Judah to him, (ii) those who were concerned about religion, and (iii) and those who cared little for either. This is why we observe the relaxation of intermarriage with the nations, and the problems with the temple service according to Ezra 9, Nehemiah 13, and Malachi 1-2.

Isaiah 56-66 corresponds to the religiously complacent, asserting that a foreigner or a eunuch who serves God faithfully from the heart is a better Jew than one whose bloodlines are perfect but whose relationship to God is carried out with a minimum of effort or reflection at best. Another theme which, like the previous one, plays up a contrast is the inability of human beings to bring about the promised salvation but the complete ability of God through his Spirit to do so. Thus, if Isaiah 40-55 speaks of hope to a people who fear that they are cast off, Isaiah 56-66 is a call for a realized righteousness from a people who have lapsed into a careless dependence upon position.